Ukiyo-e: History, Evolution, Process, & Stylistic Characteristics

Ukiyo-e, meaning ‘pictures of the floating world,’ is a well-known Japanese painting and woodblock print style. The Buddhist term ‘ukiyo’ originally described the sadness and transience of human life. Later, the phrase came to describe the fashion, lifestyle, and urban culture of Japan. The unique aesthetic and process of ukiyo-e earned the style international renown.

This September, Christie’s Important Japanese Art sale will feature several woodblock prints by ukiyo-e masters, including Katsushika Hokusai (1760 – 1849), Toshusai Sharaku (1794 – 1795), and Utagawa Hiroshige (1797 – 1858). The auction starts at 10:00 AM EDT on September 21st, 2021. Learn more about the ukiyo-e genre before the sale begins.

The Rise of Ukiyo-e

The Japanese art of ukiyo-e has its roots in the city of Edo (modern Tokyo). Before the early 1600s, the country suffered centuries of civil war. The Tokugawa shoguns successfully established a long period of peace in Japan. Under their rule, Japan thrived and flourished throughout the Edo period (1603 – 1868).

This military regime established a social hierarchy that divided society into four classes: warriors, farmers, craftsmen, and merchants. With no political power in hand, the economically powerful merchant class turned to art and culture. During this period of peace and prosperity, Japanese art found a new audience with the rising middle class. It aided the rise of ukiyo-e, a style that greatly appealed to the social class of merchants and craftsmen.

Previously, most painters only produced commissioned paintings and illustrations. The elite class determined the style and content of these artworks. In contrast, ukiyo-e was the art of the masses. It vividly documented the city life and romantic landscapes of the Edo era. These idyllic narratives also captured beautiful courtesans, theater actors, and the sensory pleasures of urban life. The prints were initially considered ‘low’ art forms, created by and for the merchant class. Soon, ukiyo-e prints were known as world-class works of art.

Evolution of Complexity in Ukiyo-e Prints

The earliest ukiyo-e artists were painters inspired by the Japanese ‘yamato-e’ painting style. Many ukiyo-e prints started as paintings, illustrations, and scrolls. It was Hishikawa Moronobu (1618 – 1694), a Japanese illustrator, who introduced woodblock printing to meet the increasing demand for ukiyo-e prints. His monochromatic works included daily lives, historical events, landscapes, beautiful women, poems, and famous stories.

Most early ukiyo-e prints were monochromatic. However, when special commissions demanded colors, artists colored these prints externally. Colored prints from the early 18th century were hand-tinted orange, or occasionally green and yellow.

By 1744, color printing with multiple woodblocks was in vogue. Green and pink were the earliest colors. However, in 1765, Suzuki Horunobu (1725 – 1770) introduced a complex color design, known as ‘nishiki-e,’ meaning ‘brocade pictures.’ Colored woodblock prints soon became the dominant style. By the late 18th century, ukiyo-e reached its zenith with brilliantly colored prints. Masters like Katsukawa Shunsho (1726 – 1793) made portraits of Kabuki actors, while others like Kitao Shigemasa (1739 – 1820) primarily depicted women and contemporary urban fashions.

By the turn of the century, ukiyo-e artists focused on landscapes, nature, birds, and travel scenes. Landscape emerged as a genre of its own, mainly through the works of Katsushika Hokusai and Utagawa Hiroshige.

Western art inspired Hokusai. His Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji (1831 – 1834) also included a now-famous print— The Great Wave off Kanagawa (1831). Hokusai’s volume elevated the widespread landscape genre in Japanese woodblock printing. Subsequently, other masters like Keisai Eisen (1790 – 1848), Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1798 – 1861), and Utagawa Kunisada (1786 – 1865) followed Hokusai. They went on to popularize landscape woodblock prints.

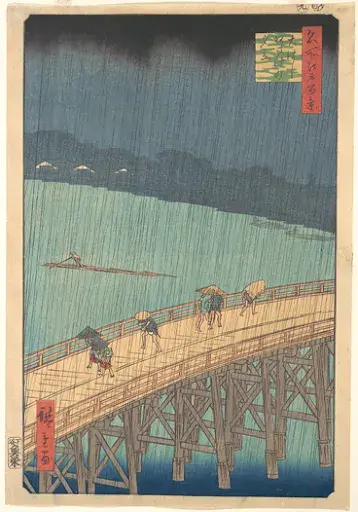

Another master artist, Utagawa Hiroshige (1797 – 1858), was best known for his travel series such as The Fifty-three Stations of the Tokaido (1833 – 1834). His works mainly featured birds, flowers, and landscapes.

Following the deaths of many ukiyo-e masters, the style suffered a sharp decline in popularity. The Meiji Restoration of 1868 delivered the final blow to Japanese woodblock prints. However, the ukiyo-e genre experienced a revival during the 20th century. Western techniques such as etching, screen printing, and mixed media started to mix with ukiyo-e to create new styles, which continue to evolve today.

The Process of Ukiyo-e

Ukiyo-e prints required the collaboration of four people— a publisher, an artist, a block-cutter, and a printer. The publisher first commissioned an artist for an original design. The artist would draw a preparatory sketch called ‘shita-e.’ The block copyist or ‘hikko’ then traced the shita-e sketch onto very thin paper and pasted it on a woodblock. The hikko cut the paper to create the key block. The block-cutter carved the design into a block, commonly made of cherry wood.

They then applied ink to a woodblock and rubbed a sheet of dampened paper, called the ‘key print,’ until the impression transferred. In the next step, the artist would choose the colors for the print. They carved a separate block for every color, thus repeating the entire process each time with a different pigment.

Next, the blocks were sent to the printer, who rubbed the dyes and transferred each impression onto mulberry paper. The printer could complete numerous rubbings on various woodblocks. In the final step, the team made print sets that numbered up to 200. Reproductions, often thousands in number, could be made until the woodblock carvings wore out. Because ukiyo-e prints were cheap to produce in large numbers, the masses could widely enjoy the works.

Stylistic Characteristics

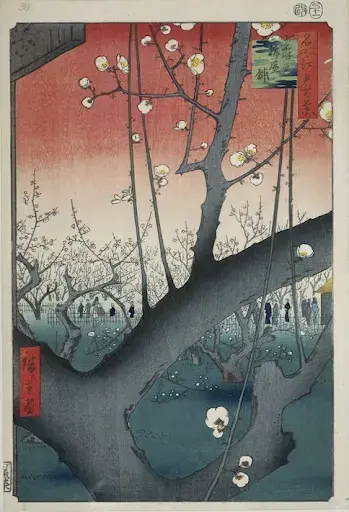

In line with its mass appeal, ukiyo-e focused on the daily life of the people. Ukiyo-e images frequently capture a story or narrative. The artists drew birds, animals, landscapes, and people of the lower social classes. The genre is also characterized by a rich color palette. Stark blacks, vivid blue and greens, and radiant reds are some of the most prevalent colors of woodblock prints, as seen in Andō Hiroshige’s The Plum Garden in Kameido (1857).

Another stylistic feature of woodblock prints is bold lines, strong shapes, and graphic designs. A fine example of this is Torii Kiyonaga’s Playing with Fans (1778). The artist prioritizes bold colors and shapes over a realistic perspective.

Several works by ukiyo-e masters will come to auction with Christie’s on September 21st, 2021. The sale starts at 10:00 AM EDT.

Want to know more about ukiyo-e masters? Check out Auction Daily’s profile of Japanese ukiyo-e master Utagawa Kuniyoshi.