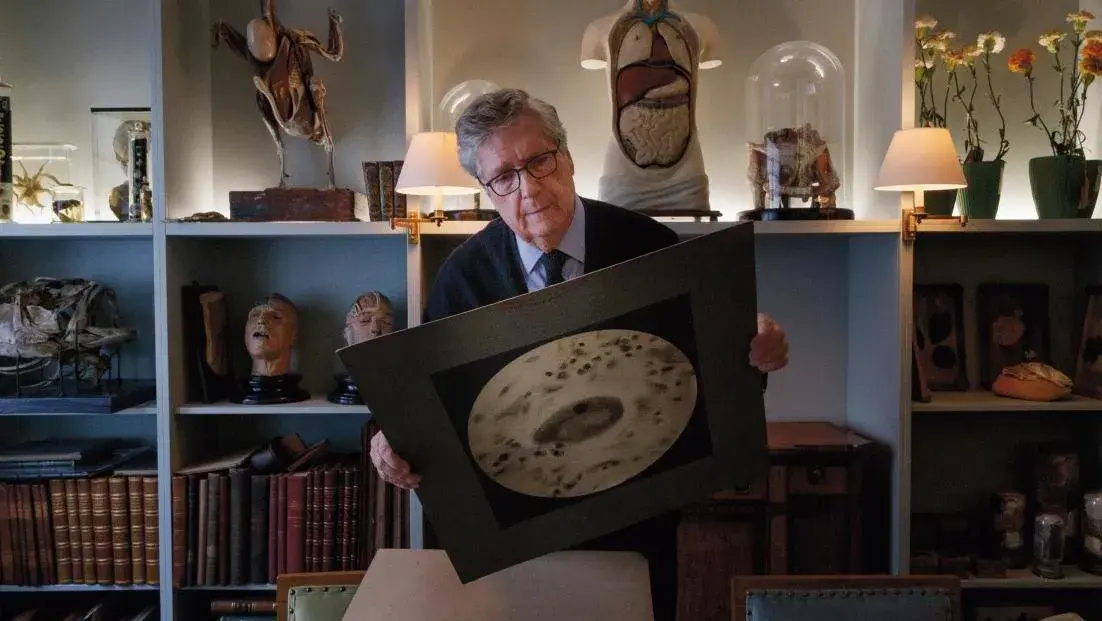

George Loudon Exhibits His Cabinet of Curiosities in Venice

This London-based collector is particularly fascinated by the objects, illustrations and educational aids used to teach the natural sciences in the 19th century. Part of this collection of 300 pieces is to be exhibited in Venice.

How did your collection come about?

I’ve always been a collector, but I never consciously chose a particular field: I just began collecting. As a child, my love of woodwork led me to collect objects connected with this art. At university, my interest turned to the caricatures of James Gillray and Thomas Rowlandson. When I lived in Indonesia from 1969 to 1971, I became fascinated by Ming Chinese ceramics. I began collecting seriously in the late 1970s, while working in the banking sector. With help from a Dutch artist friend, I decided to focus on young contemporary artists, which fuelled my need for something visible and concrete I wasn’t finding in my work.

How did you move into the world of cabinet of curiosities?

I used to describe my collection as a leisurely trip down a river, looking to left and right at what was happening on either bank, selecting an artist here and there and accepting that I might miss an important one hidden among the others. I’d say it was like “taking the outer curve of the river, looking for deep water”, trying to acquire difficult works often lying around unsold in a gallery’s storeroom. I wasn’t really looking for a new area of collecting. It just happened. I confess I gradually lost my enthusiasm for contemporary art when I felt I really wanted to know more about science. So I read a lot of books by and about Darwin, Wallace, Cuvier, Lamarck, Bates, Haeckel and so on. And I was struck by some of the visual elements, illustrations and models these 19th-century scientists used for presenting their discoveries. I was dazzled by the beauty of some of them, and I began to search for this kind of thing in museum and university storerooms. Over the years, I must have visited around 50 in different countries: all fascinating places. I focused on what was produced in the 19th century for teaching — educational material on the life sciences — and on pieces I found aesthetically pleasing or that had a particularly interesting history.

What are your outstanding pieces, and your favorites?

My first purchase was a set of display stands for teaching children in French primary schools. Entitled “Leçons de choses” (“Object Lessons”), it was designed by one Mr. Pitoiset, and this became the title of my book, published in 2015. My pride and joy are my two glass Blaschka pieces: the man o’war jellyfish and the Serpulidae model. Leopold Blaschka and his son Rudolf were German glassworkers famous for their glass representations of invertebrates (species that are difficult to preserve because they lose their color) and flowers for the Harvard Museum of Natural History. I also love Robert Brendel’s botanical models, various globes from Japan, some wax models of plants and fruit from Northern Italy and a set of Japanese fish paintings. We know relatively little about the creators of these objects. It’s rare for the illustrator of a 19th-century publication to be mentioned when people talk about a life science book or teaching material. I love the way designers grappled with different and sometimes new techniques and materials, from wax casting to cyanotypes.

How is the cabinet of curiosities market faring?

It’s not easy to find these objects. There are very few dealers specializing in this field. Any schools and universities that used them in the 19th century no longer do so. They are usually not allowed to sell them, anyway. I spent a lot of time visiting the storerooms of schools, universities and museums, to get an idea of what was made in the 19th century and what I should be looking for. But finding material is largely a matter of luck, and the people you know. Getting the opportunity to buy an object is a rare event, crowning a long and arduous quest. Art dealers who manage to obtain them have a limited stock, which they can only replenish with difficulty. Pieces appear by chance in medium-sized auction houses, as the larger ones have moved upmarket. So it’s a niche market, with little information circulating about it. This can be an advantage for collectors.

Your collection will soon be on show at the Palazzo Grimani in Venice: how will it be displayed?

The Palazzo Grimani provides an ideal setting, because of its historical link with Giovanni Grimani, a famous collector who had an encyclopedic interest in art and science. I gave the curator, Thierry Morel, carte blanche to work on my collection. He was assisted by Flemming Fallesen in designing the circuit. This aims to create a bridge between past and present, and a sensory experience that is both evocative and surprising, offering visitors a unique pathway to connect with history, nature and art. The public will start by entering a 17th-century princely cabinet, as it existed in the Palazzo when the Grimani family lived there. When they look at the ceiling decorations, they will immediately realize that my interests echo those of the Grimani family over four centuries ago.

Part of the exhibition is devoted to reconstructions of two Wunderkammer. What does the concept of “cabinet of curiosities” mean to you?

A “cabinet of curiosities” literally embodies the ideals of collecting in the Renaissance and Baroque periods: a time when art, science and the natural world were seen as interconnected. Voyages of discovery had brought astonishing, unfamiliar objects back to Europe. These cabinets were not only collections, but also mirrors of the collector’s mind. They ran counter to our modern tendency for specialization, with the idea that everything in the world is interconnected and can interact. Essentially, a cabinet was a material representation of a collector’s mind, aspirations and dreams. It was a truly personal space, where each object resonated with their inner world.

What would a 21st-century Wunderkammer look like?

It would be difficult to create one because, in theory, there would be nothing unknown, no real surprises regarding the precious objects on display. Perhaps objects from outer space? Or from the depths of the ocean? The real wonder would certainly come from the way the objects were presented: a job for curators like Thierry Morel.

Worth Seeing

“A Cabinet of Curiosities. A Celebration of Art and Nature.

The George Loudon Collection”

Museo di Palazzo Grimani, Venice

December 15, 2024 to May 11, 2025

museiveneto.cultura.gov.it