Critics and Curators Are Finally Coming Around to the Riotous Pop Paintings of Peter Saul. So Why Is the Market Still Lagging Behind?

The “patron saint” of Day-Glo colors is having quite a moment.

Peter Saul doesn’t fall into any of the easy categories that often define an artist’s trajectory.

He isn’t being rediscovered per se, nor is he underappreciated. He’s not really making a comeback, and he’s not a newfound influencer.

Instead, Saul is a mix of all of the above. And he may be undervalued, too.

At the age of 85, the artist, who has frequently been overlooked over the course of his six-decade career, just wrapped up a retrospective, “Peter Saul: Pop, Funk, Bad Painting, and More,” at the Musée des Abattoirs, a modern and contemporary art museum housed inside a former slaughterhouse in Toulouse.

And that’s not all.

In New York, he is now the subject of “Peter Saul: Crime and Punishment” (February 11–May 31) at the New Museum, his first-ever museum survey in the city. (Owing to the artist’s prolific nature, there is virtually no overlap between the exhibitions when it comes to works on view.)

The American show has already commanded glowing reviews from Peter Schjeldahl in the New Yorker and Holland Cotter in the New York Times, and the latter called it a “well timed” and “critically acidic dirty bomb of a show.”

Playing Catch-Up

Given the enthusiastic reception, some may wonder what took so long, especially considering how long the artist has been active.

“Peter Saul has had many lives, and, in a sense, many rediscoveries,” says Massimiliano Gioni, the curator of the New Museum show.

Paul McCarthy, Mike Kelley, and Raymond Pettibon were “looking at him as a patron saint” in the 1980s and ’90s, Gioni says. And more recent up-and-comers such as Nicole Eisenman and Dana Schutz are now looking up to him as well.

But his work has never been especially palatable to wider audiences.

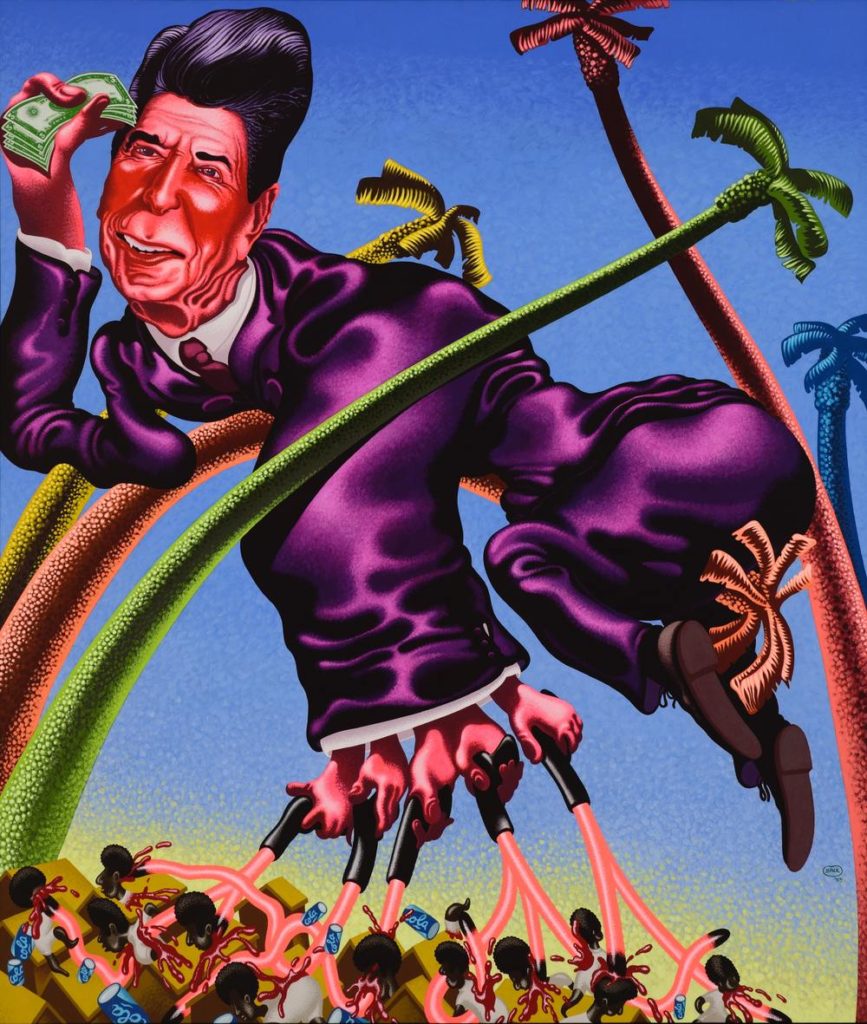

For decades, Saul’s unflinching, satirical, Mad magazine-style approach to political corruption, sexual violence, wartime atrocities, and capital punishment has shocked and confounded his audiences.

His mashups of riotous, Day-Glo colors; his grotesque, cartoonish figures; and his brazen depictions of graphic brutality and violence are not, altogether, a recipe for widespread popular success. “Saul’s effrontery,” Schjeldahl even admitted, “has long driven fastidious souls from galleries, including me years ago.”

“Peter Saul’s work makes you see the world through the eyes of the hater,” says Adam Lindemann, the owner of the Venus Over Manhattan gallery, the artist’s primary representative. (The dealer, who was exposed to Saul as a child through his friendship with the son of the late Chicago dealer Allan Frumkin, took over representation of Frumkin’s estate six years ago.)

“In a sense, the absurdity and horror of all these different things that he’s painting also allows you to laugh about them. It provides an escape valve as a way to deal with them, but it was never painted to decorate or to adorn the homes of the bourgeoisie.”

Among Saul’s best-known subjects are the American war in Vietnam; the vilification of activist and writer Angela Davis for her association with the Black Panthers; and Ronald Reagan’s disastrous (to Saul) two-term run as governor of California.

“Peter has been making crazy presidential paintings throughout most of his life,” Gioni says. “Sadly, it’s perfectly in time with the world we live in.”

The New Museum show even includes his take on Washington Crossing the Delaware (1975), a cheeky take on the image. “Saul’s 1995 parody keeps the elements more or less in place—but mostly, vertiginously, less,” writes Schjeldahl. “That boat is doomed.”

Notably, the painting comes from the collection of Brian Donnelly, aka KAWS—and it isn’t the only one lent by the street artist and market darling to the exhibition. Eleven other works from his collection (out of 60 works on view) are present at the New Museum. Another big Saul collector, Andy Hall, has lent 13 works.

A Lagging Market

Indeed, the list of lenders and supporters to the show reads like a who’s who of high-profile institutions and cognoscenti, from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Whitney Museum, and the Hirshhorn, to lead supporters like Almine Rech and Lindemann.

But even though the work is now striking a chord with a broader audience and finding critical and institutional support, the market is far less hot on Saul than it is on his peers and even the much younger artists who count themselves as his admirers.

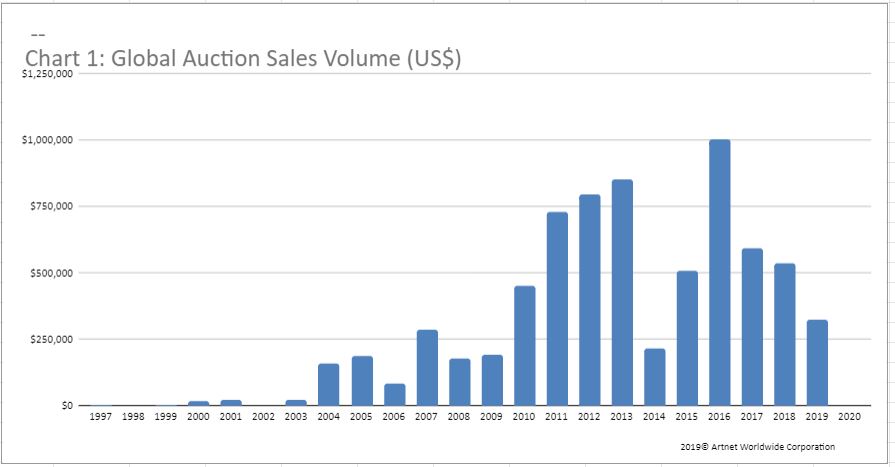

According to the Artnet Price Database, Saul’s current record at auction is $575,000, set in Chicago at Leslie Hindman in 2016 for Saul’s Guernica (1974), his take on Picasso’s epic 1937 painting.

The second-highest price of $457,500 was achieved at Christie’s Paris in December 2013 for Mad Doctor (1964), followed by $338,500 for Ice Box (1963) at Christie’s New York in 2012. Of the 223 works cited by the Artnet Price Database, only 13 examples, most from the 1960s and ’70s, sold for prices above $100,000.

Zachary Wirsum, a Postwar art specialist at Leslie Hindman, says that because of Chicago dealer Allan Frumkin’s longtime support of the artist, works tend to concentrate in Chicago and the Midwest. Saul’s Guernica, for example, came from an estate in St. Louis, and its size and art-historical subject matter generated a lot of enthusiasm.

“Collectors really like his work,” Wirsum says, estimating that he has been involved in the sale of roughly half a dozen Saul works. “It’s rare to see people parting with them.”

But the market is not especially steep.

“You can get an excellent painting for $400,000,” said Michael Baptist, a Postwar and contemporary art specialist at Christie’s. “Compared with other artists, that is not that much money.”

Market activity tends to follow a pattern: single works emerge from private collections and get quickly snapped up by buyers who already own Saul works in depth. That consolidation means that fewer works come up for sale, Baptist says.

Nevertheless, he says that inquiries have been on the rise, especially in private sales ahead of the New Museum show. “Collectors who had not been paying attention are now coming and asking about Saul, which is a good sign.”

Another thing that may boost the Saul market is the overall growth of interest in figurative art in recent years, as well as the contemporary political climate.

“He is maybe America’s best figurative political painter,” Baptist says. “His depictions of Trump don’t come off as something of the moment. When you see them in the context of his other political paintings, it looks fresh and fits so well into his art.”