The Victorian painter’s canvas conveys a moralizing message, while paying homage to his teacher Titian.

Estimate: €150,000/200,000

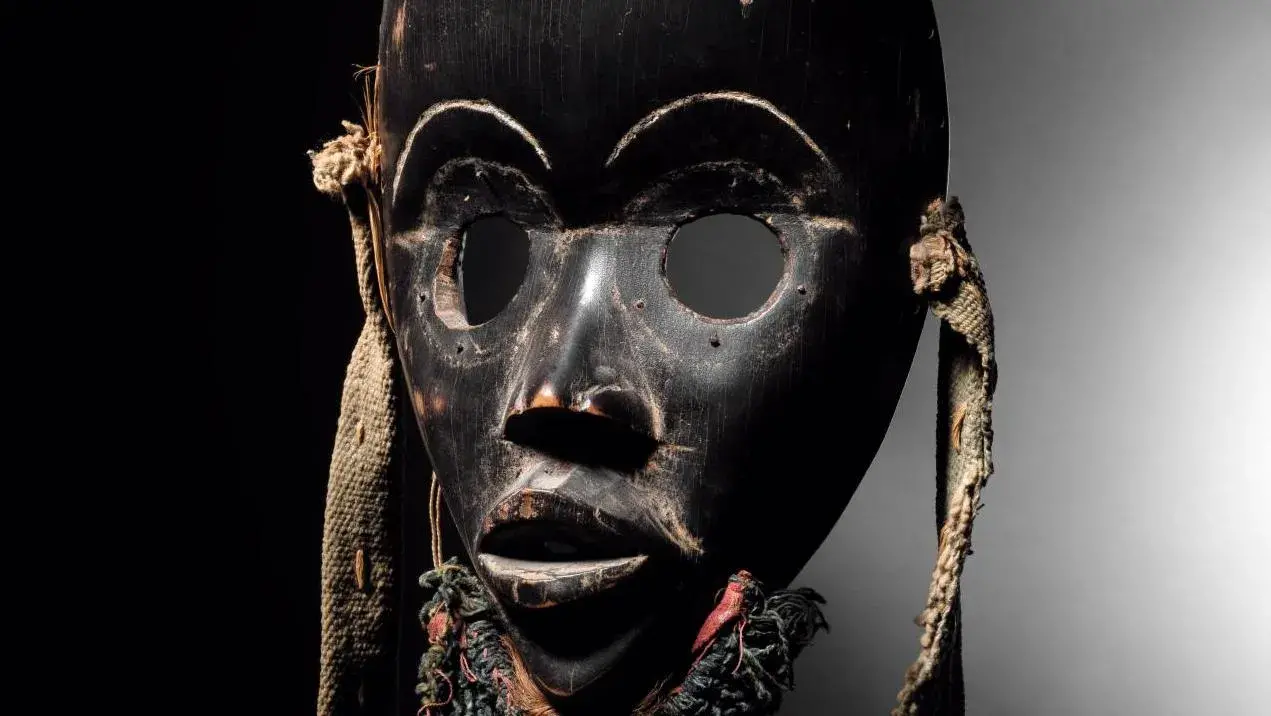

There is no overt provocation in Salomé’s demeanor. Seated, a vague air of defiance in her frontal gaze, she lifts a piece of cloth concealing a rich gold dish in which the head of John the Baptist is visible. Behind her, a young soldier cleans the bloody blade of the sword used for the sinister task, while at her feet, a wolf licks its paws contentedly. This is not the dancing, seductive Salome — as portrayed by Gustave Moreau, among others — but a woman proud of her accomplished task, yet depicted with a hint of density. The composition is meticulous, large-scale and unmistakably the work of a master. But which one? The only drawback is that it is neither signed nor dated. Looking at the work, one is irresistibly reminded of the Pre-Raphaelites, and its recent discovery in Italy — a kind of art-historical wink — makes this hypothesis seductive. However, if it was indeed painted by an English artist, Mark Bills, former Chief Curator of Paintings and Drawings at the Museum of London from 2001 to 2006, and Curator of the Watts Gallery in Guildford from 2006 to 2013, attributed it to George Frederic Watts. The Victorian art specialist puts forward several arguments in support of this hypothesis, not least the influence of Titian. Watts was fascinated by the Venetian master, whom he discovered on his second trip to Italy in 1853, the presumed date of the painting’s conception. The work’s composition and color effects — particularly that of Salome’s red dress — compares with Titian’s 1515 painting of the same subject, now in the Galleria Doria Pamphilj in Rome. The face of Herodias’ daughter, with its powerful symmetry and prominent jawline, is characteristic of Watts’ aesthetic, and can be found in several of the artist’s female portraits. The closest is Lady Ashburton (1857, location unknown), whose features are almost identical. But the most decisive element is the head of St. John the Baptist, for which it is arguably a self-portrait of Watts. A photograph taken by James Soame in 1854 shows him with the same full beard and similar elongated face. Finally, the idea that Titian might have done the same with his Salome of Rome (accepted by a number of art historians, including Erwin Panofsky) may have made this idea attractive to Watts.

More about

Gustave Moreau (1826-1898)

The Moralizing Work of an Austere Painter

The Victorian era was not exactly a carefree time. A certain puritanism was de rigueur, conveyed by the powerful Church of England. Although he was not an active member, Watts often painted biblical subjects, by virtue of his belief in improving the character of those who looked at his work. This idea, widespread in 19th-century Britain, explains why the majority of Watts’ works carry a moral and ethical message. The image of Salome, repeatedly used by painters since the 16th century, is a case in point. For good measure, Watts added a wolf to the young woman’s foot, an animal symbolizing the thirst for power as well as a form of lust. It was a fitting subject for an artist with a mystical bent and a well-established reputation. In 1892, the Pall Mall Gazette wrote of him that “Watts was serious, lacked a sense of humor and was politically radical – twice refusing the title of baronet”. Quite a character! It wasn’t all doom and gloom, however, as the same newspaper pointed out: “He was very sensitive to the appalling living conditions of the urban poor. Watts considered the fact that the country’s upper classes were taking huge sums of money they hadn’t earned to be a great evil.” He thus devoted four paintings to social tragedies in London and Ireland. Watts’ love life was rather tumultuous, as the Pall Mall Gazette points out: “In middle age, this serious and already elderly painter made a short-lived and totally disastrous marriage with the great actress Ellen Terry, then in her teens.” Although the union lasted only a year, Watts used the young girl as the model for his portrait Choosing (National Portrait Gallery). His second marriage in 1886 to Mary Fraser Tylter, thirty years his junior, was a happy and artistically fruitful one. An excellent portraitist, Watts was a celebrity during his lifetime, being the only artist to be among the first twelve recipients of the Order of Merit, newly instituted in 1902. A complex artist, whose works touched the heartstrings of his time.

Salomé, a Woman Misunderstood

“Whatever you ask of me, I will give you, even if it’s half my kingdom”. So says the tetrarch Herod Antipas — according to the Gospel of Saint Mark — to Salome, daughter of Herodias. She had just performed a dance that pleased her great-uncle — or uncle and/or father-in-law, depending on tradition. The price of this dance is well known: the head of the holy preacher, requested by… Herodias. In the Scriptures, Salome is referred to by the Greek word korasion, a diminutive of korè (young girl), as she was no more than 11 or 12 years old at the time. It was not until three centuries later that she metamorphosed into an erotic figure in a sermon by Saint Augustine, an image that would endure through time, and conveyed by artists. Watts is no exception to the rule, highly inspired by figures of powerful women. He returned with another version of the same subject in an 1885 painting (private collection). The vision is very different: Salomé is triumphant, looking straight at the viewer and brandishing Herod’s ring, thus exonerating herself of all guilt. Seductive and bewitching, Salomé epitomized the castrating femme fatale of the late 19th century. Although her popularity subsequently waned, she has yet to be redeemed.

Paintings – Furniture and objets d’art

Wednesday 18 December 2024 – 14:00 (CET) – Live

Salle 16 – Hôtel Drouot – 75009 Paris

Paris Enchères – Collin du Bocage