The Torlonia Collection, a Treasure of Italian Heritage at the Louvre

For the first time ever, Rome’s most secret collection is leaving Italy to be shown at the Louvre. Masterpieces that were in darkness for nearly 50 years will come out into the light.

© Fondazione Torlonia

The Torlonia marbles are crossing the Alps. An exhibition at the Louvre of the world’s largest private collection of ancient sculptures, once belonging to a 19th-century Roman prince, is being organized by Cécile Giroire, Head of the Department of Etruscan, Greek and Roman Antiquities, and curator Martin Szewczyk. This treasure of Italian heritage will grace one of the museum’s most beautiful settings, Anne of Austria’s newly restored summer apartments: an obvious choice because they have housed the permanent collection of ancient sculptures since the museum was created. Inaccessible to the public for decades, the masterpieces of the Torlonia Collection have set out on a tour of exhibitions-events in Rome, Milan and now Paris, the first stop outside of Italy. For its owners, this is a return to distant origins. But the dynasty that was one of the papacy’s most reliable financial backers has its roots in France.

© Fondazione Torlonia

Taste and Money

Marin Tourlonias (1725-1785), the son of a merchant and farmer in Auvergne, moved to Rome at age 25. He Italianized his name and began selling cloth, but it was the world of finance that saw him launch his family’s meteoric rise. Preferring the sound of clinking coins to that of rustling fabrics, Torlonia became a pawnbroker while continuing to work in the cloth trade. His son Giovanni (1754-1829) founded a bank that quickly became the most prosperous one in the city. Stendhal described his lavish parties in Walks in Rome. The writer was not the only one fascinated by this man driven by “his passion for money and art”, whose son Alessandro (1800-1886) quickly earned the nickname the “Roman Rothschild”. The early 19th century abounded in opportunities to strike it rich. Alessandro left his role as supplier to the armies of the French Republic and became the pope’s banker: every time there was a historical crisis or regime change the family took another step up on the ladder of wealth. By 1810, they were already among Rome’s 20 leading clans. Aristocrats soon stopped looking down on them as bourgeois parvenus: it is hard to sneer at one’s creditors. In exchange for loans, the Torlonias requested artworks as collateral, and soon filled their many palaces with them. Frequent visits to auction rooms enriched their collection, which began in 1800, when Giovanni bought about a hundred pieces from sculptor and restorer Bartolomeo Cavaceppi, whose studio was a mandatory stop on the Grand Tour. At an 1825 sale, he purchased 270 works, some from the 17th-century’s most prestigious collection of ancient sculptures, owned by Marquis Vincenzo Giustiniani, a friend and patron of Caravaggio.

A Legend Was Born

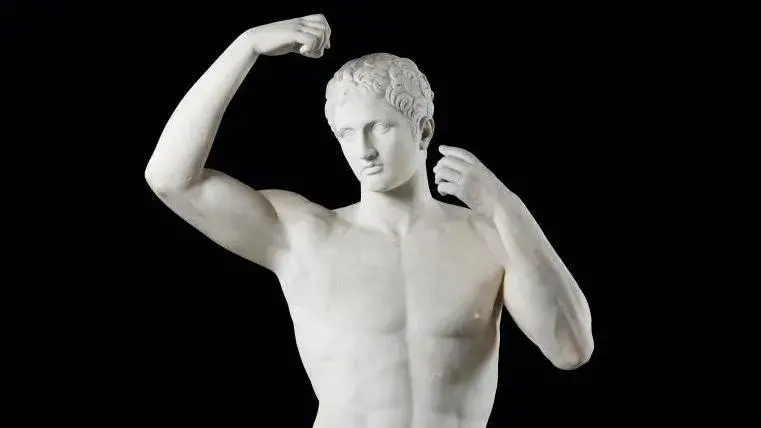

High-quality pieces flowed into their collection. Discoveries made during excavations on their lands in Lazio joined sculptures included in the dowries of daughters of the high nobility. The Torlonia’s ask for their hand in marriage, while putting theirs own hands on their family’s art collections. In 1866, Alessandro bought Cardinal Albani’s villa and collection of antiquities in Rome (see Gazette 2023 no. 25, page 224). But money was not enough to reach the apex of high society: the Torlonias lacked a title. The pope obliged by raising them to the rank of marquises, then princes, then Roman patricians. In 1876, the family allowed a privileged few to ogle their riches. Their palace on via della Lungara, near the Tiber, became one of the world’s first private houses open to the public. In 1881, photographs of the collection’s 623 marble and alabaster statues appeared in a detailed catalog. Dozens of Hercules and Venuses could be seen alongside hundreds of busts of emperors and philosophers, while copies of Greek statues mingled with sculptures of animals, like the ancient Caprone restored by Bernini in the 17th century. After being scattered for safekeeping during the Second World War, the works returned to via della Lungara. In the 1970s, the building’s roof was in need of repair. Prince Alessandro Torlonia (1925-2017) took advantage of the opportunity to convert the property into nearly 100 luxury apartments. The collection was stored in the palazzo’s cellar, where it slumbered for nearly a half-century, becoming the stuff of legend, shrouded in mystery and fueling rumors. The sculptures were said to have been put willy-nilly in damp cellars in conditions that endangered them. Scandalized Italian journalists wrote that Alessandro was planning to sell the pieces, plundering the country’s artistic heritage. The prince brushed aside the criticism and accusations. Alluring offers, such as the €125 M made by Silvio Berlusconi, left him as cold as marble. He did not yield to the Italian government’s generous advances until 2005.

© Fondazione Torlonia

Resurrecting a Treasure

His treasure was compared to Tutankhamun. “It was as if the prince had sealed up the statues in a tomb, forbidding access to anyone,” says Anna Maria Carruba, the head of the restoration team. In fact, darkness and a thick coat of dust perfectly preserved the precious vestiges. The slightest details on their condition and the methods used in the past to restore them were recorded. This painstaking job, which was funded by jeweler Bulgari and promoted by the Torlonia Foundation, stemmed from Prince Alessandro’s desire to allow future generations to enjoy his collection. Each exhibition is an opportunity to learn more about this precious heritage. Twelve pieces have been restored for the Louvre exhibition. But where will the 623 sculptures end up once their world tour is over, after stops that could include London and New York? The question has been in the air since the 1960s. The City of Rome and the Italian government have tried to answer it with three museum projects, none of which amounted to anything. Nor did Prince Torlonia’s dream of building a museum entirely dedicated to his collection. The Ministry of Culture recently considered, with the Torlonia Foundation, moving them into the Palazzo Silvestri-Rivaldi, near the Coliseum, which is undergoing a renovation due to end in 2025. No decision has been made yet, but one thing is sure: after spending a half-century in darkness, Rome’s last great princely collection will never again be out of the spotlight.

WORTH SEEING

“Masterpieces from the Torlonia Collection”, Louvre Museum, Paris I

Until November 11, 2024

www.louvre.fr