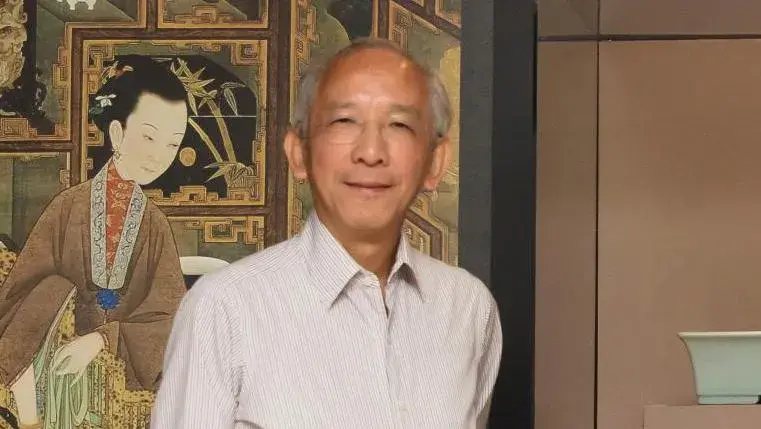

Richard Kan, Collector of Chinese Monochrome Porcelain

Published on

The Chinese monochrome porcelain collection owned by this Hong Kong patron and collector is one of the finest in the world. Part of this remarkable collection is now on show at the Musée National des Arts Asiatiques-Guimet. © Richard Kan / COURTESY of Richard Kan The name of your collection is Zhuyuetang. What does it refer to?I come from a family of tobacco entrepreneurs, established in 1907, when the Qing dynasty was still in power. This poetic name, freely inspired by the composition of the Chinese character “kan”, like my surname, means “Pavilion of Bamboo and the Moon.” It's a tribute to