Italian Renaissance Drawings at the Fondation Custodia

Published on

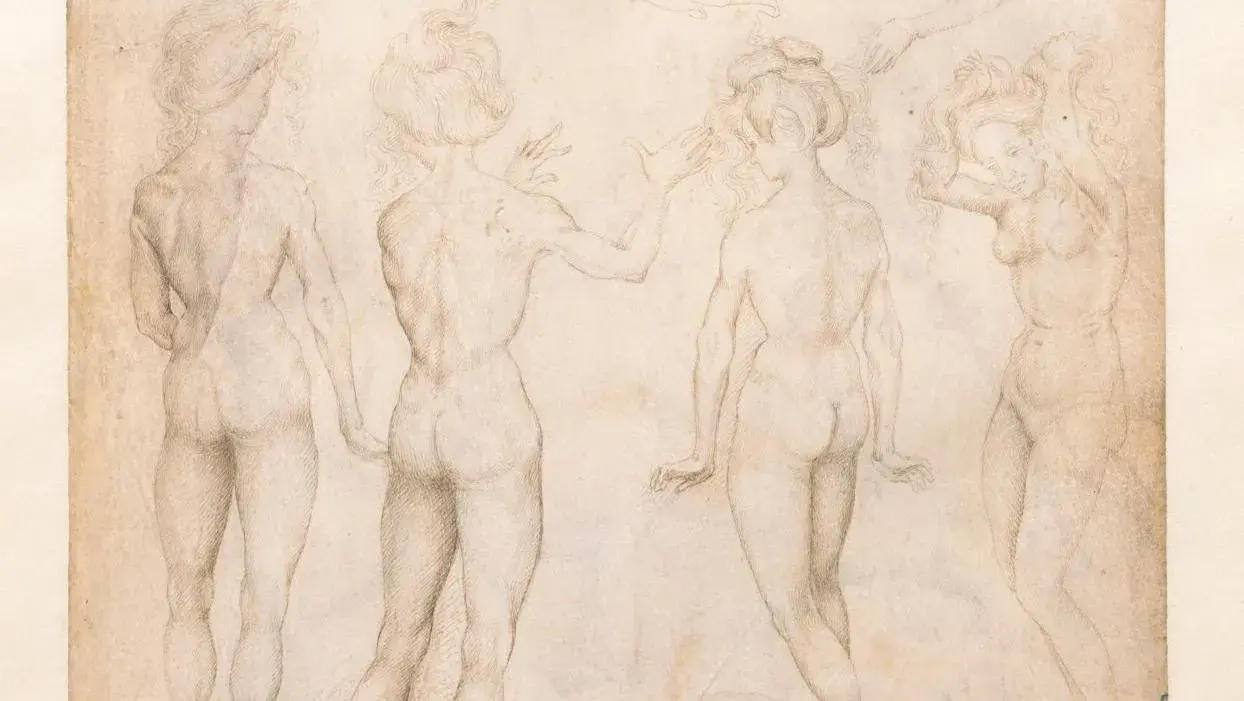

The Fondation Custodia is exhibiting drawings from Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen: 120 masterpieces in a variety of styles and techniques, showing the medium’s essential role in the creative process from the 15th century onwards. Pisanello (c. 1395-1455), Four studies of a nude woman, an Annunciation and two studies of women swimming, c. 1431-1432, pen and brown ink on parchment, 22.3 x 16.7 cm/8.7 x 6.3 in. While there are plenty of fine drawings in France’s public collections, there are only a few opportunities to see them, given their fragility: at the Salon du Dessin, in the graphic art departments of various museums