Artists In Focus: Three Free-Thinkers

If you missed them at Frieze Los Angeles, there’s still time to catch ongoing exhibitions of Do Ho Suh, Shirin Neshat and Gala Porras-Kim in Los Angeles and London. Claire Wrathall reveals why these artists should be on your to-view list

Do Ho Suh

Born Seoul, 1962; lives and works in London

Do Ho Suh once had an idea for a children’s book. In it, a traditional Korean house is lifted by a typhoon and carried across the Pacific to America, where it falls into an imposing New England brownstone with a mansard roof and a colonnaded porch, and begins to grow into what he has called ‘a baby or a parasite’.

Suh never published the book, but the story informs much of his art, not least Home within Home within Home within Home within Home, which was exhibited at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea, in 2013.

Constructed from translucent fabric stretched across a metal frame, it is a 1:1-scale model of the first building he lived in as a student at the Rhode Island School of Design, within which is suspended a model of the home he grew up in.

Suh found his US home ‘uncomfortable’. Space in Korean homes is separated by screens rather than compartmentalised with immovable walls, and there is a greater, more ‘porous’ connection with the outside world. Measuring and computing the dimensions and volumes of his American apartment, he has said, was an attempt to relate to its confines.

Wrought in sheer, often colourful polyester, and occasionally silk organza, then stitched to wire frames, Suh’s haunting and exquisitely detailed evocations of his homes and their contents were originally designed to pack flat in a suitcase so he could carry them whenever he moved.

From Rhode Island, he went on to Yale, New York, Berlin and now London. All the places he has lived have been recorded as works of art, hence his full-scale replication of the New York apartment he rented on West 22nd Street, complete with corridor, stairs and studio, now on show at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA).

Within the architectural elements, fixtures and fittings, there is something autobiographical at work, a ghostly sense of displacement and impermanence. ‘The space I’m interested in is not only a physical one, but an intangible, metaphorical and psychological one,’ he has said. These are works about memory more than material surroundings.

Yet they are also truthfully detailed, so it’s no surprise to learn that Suh once wanted to be an architect. Instead, he followed his father, the eminent artist Suh Se-ok, training first as a painter. And lately he has returned to paper, in a highly original way.

First, he stretches it over the object he wants to recreate: a phone, a hairdryer, an electrical cable and extension lead, pipework and taps. Then he makes a rubbing, in pastel or coloured pencil, that captures every contour and texture of the object’s surface, after which he uses the paper to construct intricate actual-size 3D facsimiles of these otherwise everyday things — works that are realistic in every way apart from the heft and solidity they suggest; in reality, they are as fragile as paper and almost as light as air.

Do Ho Suh: 348 West 22nd Street is on show at LACMA until 29 March

Shirin Neshat

Born Qazvin, Iran, 1957; lives and works in Bushwick, New York

Shirin Neshat has spent most of her life in exile. As a child, she was sent away to school, first to board at a French Catholic convent in Tehran, and then, at 17, to the USA.

‘I couldn’t imagine how much I would miss my family and friends,’ she told the writer Cristina Ruiz. (She still calls her mother in Iran every day.) But she made the best of it, going on to Berkeley to study fine art, and by the early 1980s — ‘an exciting time to be an artist’ — she was living in New York.

She did not return to Iran until 1990, when she was shocked, not so much by the country’s transformation from an outward-looking, ‘quite European or Westernised’ culture to a fundamentalist one, but by the extent to which her generation had been responsible for it. The work it inspired, notably a series of photographs called Women of Allah (1993–97), established what she calls her ‘voice’.

These sober, black-and-white portraits focus on the faces, hands and occasionally feet of chador-clad women. What flesh is visible is inscribed with texts of prayers and Farsi verses by poets such as Forough Farrokhzad and Tahereh Saffarzadeh.

‘Most Iranians use poetry as a form of reflection,’ she has said, making the point that, although much of it is mystical, it can also be subversive, ‘because everything you’re not allowed to say overtly you can say through poetry’.

In Speechless, below, a portrait of Neshat’s friend, the artist Arita Shahrzad, a gun points from within her hijab so that its silvery barrels might almost be an earring. The subjects may be veiled but, far from submissive, their gaze is direct and fierce.

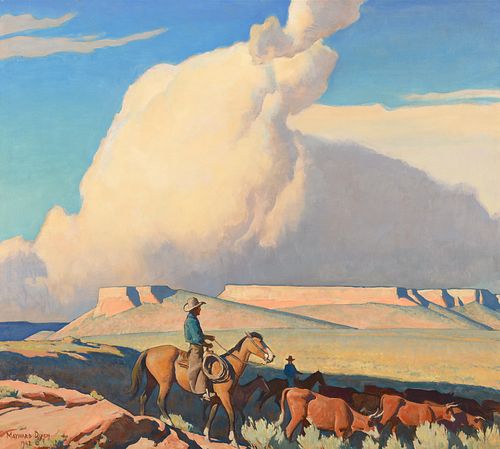

Neshat photographs landscapes and the built environment, too, and uses video as well as photography. Her latest project, Land of Dreams, consists of 111 images, this time of Americans, and a video diptych.

In the film, a photographer travels through New Mexico photographing people and asking them about their dreams. In a surreal twist, it transpires she is gathering data for a secretive team of Iranian scientists seeking to understand the American mind.

‘Think about the fanaticism of the Iranian government and the fanaticism in [the USA],’ she told The New York Times. ‘We make monsters out of each other. They demonise American culture, people and government; and the Americans demonise Muslims.’ This is what she is striving to parody, by means of ‘surrealism and absurdity’.

Shirin Neshat: Land of Dreams is at Goodman Gallery in London until 28 March

Gala Porras-Kim

Born Bogotá, 1984; lives and works in Los Angeles

After completing her MFA at the California Institute of the Arts, Gala Porras-Kim worked for an architect and became fascinated by the Zapotec language spoken by Mexican workers on construction sites. Intrigued by its sounds — and concerned, she admits, that they might be talking behind her back — she enrolled for a second master’s degree in Latin American studies at UCLA.

Her interest in the southern Mexican state of Oaxaca, where the Zapotec civilisation was one of the great flowerings of pre-Columbian culture — and, she says, ‘one of the most linguistically diverse regions in the world’ — has informed her art ever since.

Her early works focused on the language itself. She mapped its tones, made installations of its verbs, and drew 24 detailed studies of the embouchure required to produce the sounds she struggled to make (much of it is whistled).

But as her practice developed and embraced other pre-Columbian cultures, it became more conceptual. At the Whitney Biennial in New York last year, she presented a triptych of works inspired by La Mojarra Stela, a limestone slab covered in second-century carvings, excavated in 1986 from the Acula River near Veracruz.

La Mojarra Stela 1 Incidental Conjugations is a plexiglas disc in which little plaques of text are suspended in a mix of oil and water so that, as Porras-Kim said in a lecture at Harvard last autumn, they ‘fall and make these random connections that you couldn’t otherwise come up with’.

At first, one interprets it as a random abstraction of never-to-be-repeated colours and shapes. But every fragment means something, if only we knew how to decipher it.

Porras-Kim draws, paints and makes ceramic sculpture, too, some of it inspired by LACMA’s pre-Columbian collections. This has led to an interest in museology and curation, in the philosophical differences between works of art and ethnographic objects. At what point, she seems to ask, does the installation of a collection become a work of art in itself? And who really owns these found objects?

It was only a matter of time before she was asked to curate an exhibition herself, hence the current MOCA display of works she has chosen because each defies conservation and is destined to deteriorate or disappear. It’s a theme that reflects her interest in mutability — evident in works such as Archimedes Death Ray and Untitled (Water Erosion) — and in controlled, and uncontrolled, destruction.