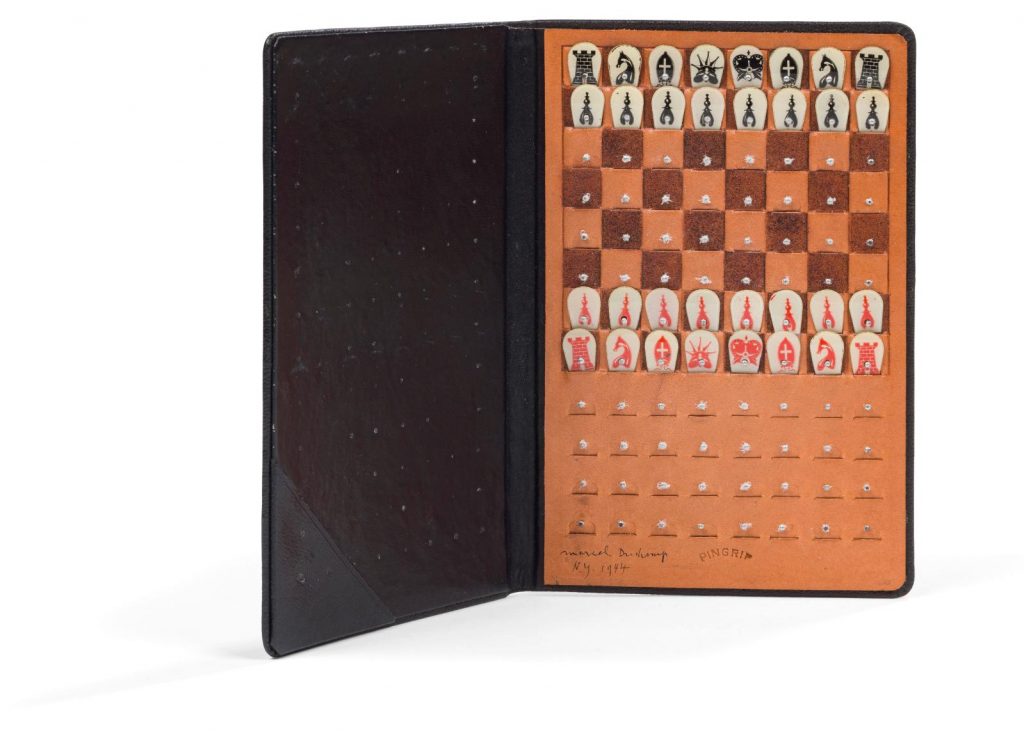

A ready-made by Marcel Duchamp, chess champion, for Dolorès Vanetti

Fascinated by chess since childhood, Marcel Duchamp incorporated this fascinating discipline into his art. This ready-made, produced in New York in 1944 as a gift for his friend Dolorès Vanetti, is a case in point.

Estimation : 120 000/150 000 €

Quite a symbol. Knowing the importance of chess in Marcel Duchamp’s life, it’s easy to understand the importance of this ready-made, known as “helped” because the artist intervened in it more than usual. In 1944, he acquired around twenty-five copies of this pocket chessboard, which he particularly liked because he always carried one with him, wanting to be able to play anywhere. He made one notable and essential modification : the insertion of small nails to give the pieces greater stability. His mark was then affixed : “Marcel Duchamp N.Y. 1944”. In December, Duchamp presented this new creation at a chess exhibition at the Julien Levy gallery. Some of the pieces are now in the collections of major American museums, including the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Art Institute of Chicago and the Yale University Art Gallery. The artist also offered a number to friends, such as American chess player and New York tournament director Harold M. Phillips, whose set sold for €358,577 on November 15, 2017 in New York (Sotheby’s).

This one was given to Dolorès Vanetti (1912-2008), and has remained in her family to this day. Initially an actress in France, in 1936 she met her husband, Théodore Ehrenreich, a future doctor. Fleeing the war, the couple settled in New York in 1940. Now a journalist, she worked in radio, notably for the Office of War Information on The Woman show. She also wrote a column for Vogue and poems for André Breton’s VVV magazine. It’s a period of wild emulation in New York, where artists are brought together by the war, especially the Surrealists. Jean-Paul Sartre was part of this circle, and Dolorès Vanetti was to have a love affair with him from 1945 to 1950. She introduced the philosopher to Calder, Breton, Dos Passos and Marcel Duchamp. Between 1940 and 1944, Duchamp lived in Greenwich Village. By then, he was fully back at work, even though he had announced in 1923 that he would devote himself to chess after leaving Le Grand Verre unfinished. Chess was omnipresent in his life. As a fine strategist, he did himself the honor of transforming this pocket chessboard into a ready-made, thus setting it up as a work of art.

A game of chess, a work of art in its own right

Marcel Duchamp appreciated chess as much for the intense reflection it demanded as for its aesthetics, the shape of the pieces and the chessboard. He was introduced to the game as a child at his family home in Blainville-Crevon, Normandy, by his two older brothers, Raymond Duchamp-Villon and Jacques Villon. It soon found its way into his work, as early as 1911, with Portrait de joueurs d’échecs (Philadelphia Art Museum). The profiles of his brothers are repeated, suggesting the evolution of their attention over time, the pieces floating in space between them like images of their mental projections. During the nine months he spent in Buenos Aires in 1918-1919, the artist became increasingly involved in chess, before devoting himself entirely to it between 1923 and 1933. He became an excellent player, becoming champion of Haute-Normandie in 1924 and a member of the French team on four occasions at the Chess Olympiad from 1928 to 1933. In 1932, he even published a reference work on endgames, poetically entitled L’Opposition et les cases conjuguées sont réconciliées (published by L’Échiquier…). Further proof that, for Marcel Duchamp, a chess game was a work of art in its own right, with its own creative process, gestures and reflection.