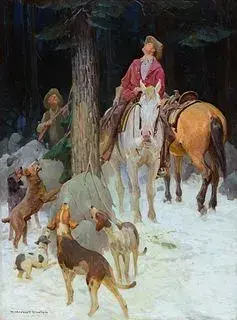

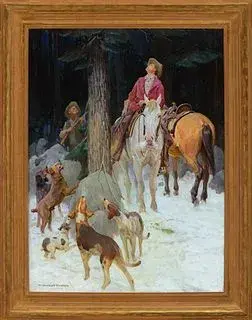

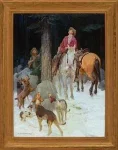

William Herbert Dunton (1878–1936) — Treed (ca. 1915)

Winning Bid: $1,200,000

William Herbert Dunton (1878–1936) — Treed (ca. 1915):

William Herbert Dunton (1878–1936)

Treed (ca. 1915)

oil on canvas

40 × 30 inches

signed lower left

Treed will be included in Michael R. Grauer’s forthcoming W. Herbert Dunton Catalogue Raisonné.

“A ‘lone wolf?’ Yes, to the human. But I am far from alone for with me constantly is my art in which I am absorbed and back in the hills with a saddle horse and one to pack and with a hound or two I’m quite content; with the trees and streams and the deer, elk and bear all about me.” – William Herbert Dunton

According to art historian Michael R. Grauer, “Unlike his fellow artists in Taos, New Mexico, and most of his peers in Western art, W. Herbert Dunton was a true outdoorsman. Dunton worked annually in the West as a cowboy and hunter from 1896 to his first summer in Taos in 1912. Because of his work as a ‘puncher’ and hunter from Montana to Mexico, at one time Dunton was one of the most prolific and popular Western and outdoor illustrators in the United States.

“Born near Augusta, Maine, he hunted and fished with his maternal grandfather as a child, and later carried a sketchpad along with his rod or rifle. In 1896 ‘with a … new Winchester’ he traveled to Montana where he became a contract hunter for ranches in Park and Musselshell counties for two years. Back in Boston then New York, he wrote and illustrated articles for outdoor and sporting magazines. He became friends with Philip R. Goodwin, the most popular wildlife and sporting artist in America by the early 1900s.

“After first visiting Taos in 1912, he moved there in 1915. He continued hunting big game in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, including deer, elk, bear, and mountain lion. Dunton also became Taos Fish and Game Protective Association president in the late ‘teens as his views toward wildlife in New Mexico evolved. While in Kansas City, Missouri, for an exhibition of his work there in 1924, Dunton delivered a radio address titled ‘Hunt But Don’t Kill All,’ lamenting the loss of game in New Mexico and the need to protect what remained.

“During pack-horse trips into the Sangre de Cristo Mountains in the late 1920s and early 1930s, he mainly made ‘dry-hunts,’ ‘taking’ game with a thumb-box of oil paints and small canvas panels. His last major paintings from 1930 to 1936 emphasize big-game animals – elk, deer, and especially bears – in simplified, stylized landscapes characterized by rich color.

“Treed is an excellent example of Dunton’s hunting paintings created while he still maintained his connections to Boston and New York publishers such as Forbes Lithograph Manufacturing Company. The most prominent lithographic house for the firearms and ammunition trade, Forbes printed advertising posters and calendars for firearms makers Hopkins & Allen, Marlin, Remington, Savage-Stevens, and Winchester.

“For about his first ten years in New Mexico, Dunton actively hunted and acted as a hunting guide. One of his frequent hunting partners was Elliott S. Barker (1886-1988), particularly on mountain lion hunts. Barker worked as a professional guide and hunter near Las Vegas, New Mexico, for two years before becoming a forest ranger in the Jemez National Forest in Cuba, New Mexico, and the Pecos National Forest in Pecos, New Mexico, beginning in 1909.

“Treed probably depicts a mountain lion hunt in which Barker may have been the inspiration for the younger hunter in the red coat mounted on the white horse. Barker was often photographed with a white horse. The figure of the older hunter in the background may have been inspired by Dunton’s friend and fellow hunter Bingham E. ‘Bing’ Abbott (1875-1948). The dogs include hounds, an Airedale, and a terrier.

“Writing to a patron in 1926, Dunton discussed the source of his ideas for hunter, hunting, and outdoor paintings: ‘The inspiration for this canvas – as in my others – was my own trips in the hills.… I have depicted no particular place – as I do in few of my canvases – changing the lines of those I see in nature to make a ‘composition.’ That is where the art comes in – taking what one wishes from a place or places and knowing what to discard.’

“As far as composition for these type of figure paintings, Dunton wrote to his friend Texas artist H. D. Bugbee in 1922 advising him about how to construct his paintings: ‘you also have got to arrange them so that they form artistic masses along the lines of which the eye is unconsciously led through and back and fourth [sic] across the canvas – never out of the picture.’ This describes Treed perfectly in that the eye is led into the picture by the right hind leg of the dog, exactly at center (his tail helps guide the eye). The curve of his body up to his head point up to whatever is ‘treed’ and is reinforced by the heads of the other four dogs and the hunter in the background all gazing up. The broken branch leaning against the tree at center forms an arrow pointing up the trunk of the pine tree (that reminds us of one of Goodwin’s signature hemlocks). Then our eye is led back down to the front brim of the younger mounted hunter, around his brim and down his shoulder to the saddle horn, then cantle, then horse’s rump, down its tail to the resting hind foot angled slightly toward the centermost dog’s tail. Then our eye jumps to the tail of the foremost dog and the journey starts all over again: ‘through and back and fourth [sic] across the canvas – never out of the picture.’

“Dunton insisted upon appropriate clothing and accoutrements in his paintings, although he never descended into accuracy for its own sake. In Treed both hunters carry Winchester rifles and the mounted hunter wears Barker’s signature ‘batwing’ chaps and a hat with what appears to be a Stetson Carlsbad crease, favored about this time. The buckskin horse carries a single-rigged open-loop Western stock saddle with Sam Stagg rigging and a cantle with a Cheyenne roll.

“Dunton bathed the foreground in a general light in the forest clearing. He posed both hunters and horses and the snow-covered ground and boulders against a dark forest background. This effect presages the theatricality – even artificiality – that came to characterize his much later canvases such as McMullin, Guide (1934), that aligned his work with the Regionalist movement of Grant Wood, John Steuart Curry, and Thomas Hart Benton. This theatricality is only heightened by the mystery of what has been ‘treed.’ This air of mystery (foreboding) is an undercurrent found in the ‘predicament paintings’ of Dunton’s friends Goodwin and Charles M. Russell.

“W. Herbert Dunton’s Treed is an outstanding example of wildlife and sporting art depicting the American West. This painting would make an exceptional addition to any collection of art of the American West or wildlife and sporting art, or both.”

PROVENANCE

The artist

Forbes Lithograph Manufacturing Company, Boston, Massachusetts

Private collection, Andover, Massachusetts

View more information

ConditionSurface is in good condition. Faint hairline cracks in the trees. Small line of inpainting on the solid-brown dog’s chest. Small spots of inpainting in the snow in the lower-right corner.